“He never, ever got tired of the music”

Larry Reynolds grew up in Shanboley, Ahascragh, County Galway. He was the 12th of 13 children born to the late Cornelius and Mary (Kenny) Reynolds. Larry’s boyhood home was a well-known gathering place for music and house dancing, where there was “never a shortage of either.” He began to learn the fiddle at age 10 when his oldest brother Harry bought one for him and his sister Betty paid for lessons. He was schooled in the traditional style of East Galway, and he played for love, not money. But money was scarce and so, like many Galwaymen of his generation, Larry immigrated to Boston in 1953 at the age of 20. He fed his stomach by working as a carpenter. He fed his soul by playing his fiddle. He used his bow like a saw, to build something that would last. When Larry arrived in Boston it was at the height of the Dudley Street era in Roxbury, when numerous Irish dance halls created a vibrant dance scene that lasted into the early 1960s. He played with Paddy, Johnny and Mick Cronin from Kerry, Brendan Tonra from Mayo, and a host of American born players like Joe and George Derrane and the late banjo player Jimmy Kelly. He later formed his own groups, the Tara Ceili Band and the Connacht Ceili Band, before devoting himself solely to Comhaltas starting in 1975.

In 1954 he met and married Phyllis M. Preece, a piano player. Over the years they were blessed with 7 children (6 boys and 1 girl) 19 grandchildren and 15 great-grandchildren. Over their years together, both Larry and Phyllis imparted their knowledge of music to their children graciously hosting in their Waltham home innumerable musicians. Although he earned his living using his hands to build things, his real passion in life was to use those hardworking, coarse hands for a gentler purpose to build beautiful music.

In 1975, after having hosted the Comhaltas Concert Tour Group in 1973, ’74, and ’75 Larry along with Pat and Mary Barry, Billy Caples and John Curran, formed the Boston branch, starting at the VFW Hall in Allston, then moving to the Canadian American Club in Watertown, where it still meets today. The group’s monthly sessions and set dancing classes quickly attracted people from all genres, turning the branch it into one of the largest branches in the group’s worldwide network. Larry always noted Comhaltas as a welcome addition to Boston’s flagging Irish scene. “The Dudley Street dance hall scene had closed, followed by the State Ballroom on Mass Ave, and after that, the music went into pubs and small halls around the city, in Dorchester, Brighton, Somerville…it was all spread out,” Larry hosted one if not the first of the Irish “pub” Sessions at The Village Coach House in Brookline, which later moved to the Green Brian in Brighton until it closed which is now hosted at The Burren in Somerville.

In 1984, Larry began broadcasting a one-hour radio program on Boston radio station WNTN, 1550 AM on Saturday mornings, the Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann Hour, a show that brought traditional Irish music and banter into the homes of listeners worldwide where his son Sean alongside him for many years played to the listeners content much of his love for traditional, but more so the East Galway Style of music.

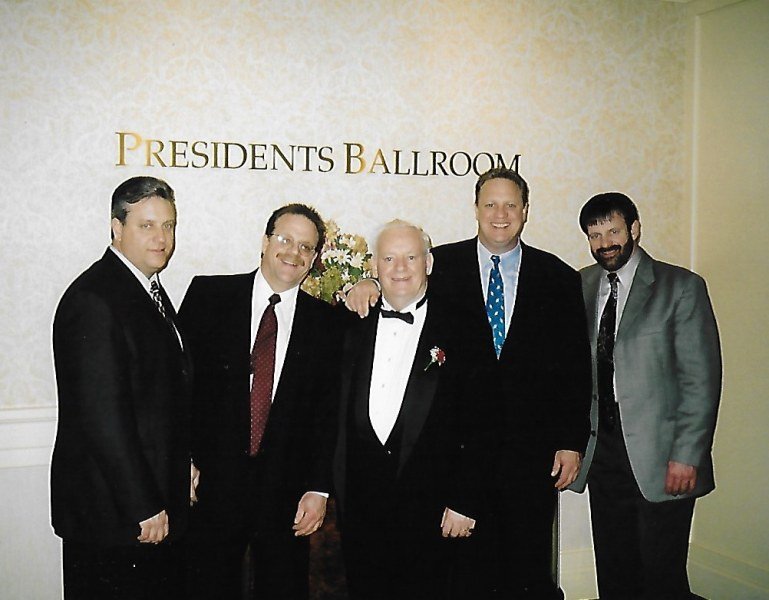

While serving as the founding member and Chairman of Boston’s “Reynolds-Hanafin-Cooley” branch until his passing, Larry was also the treasurer of the North American Provincial Council of CCE. Larry was inducted into the organization’s Hall of Fame in November of 2002. In 2003 Harvard University’s Celtic Department honored him for ‘the enormous contributions to Irish culture in Boston.’ He was honored by the Irish Cultural Centre of New England. In 2006 he was named one of the Top 100 Irish Americans by Irish America Magazine in New York.